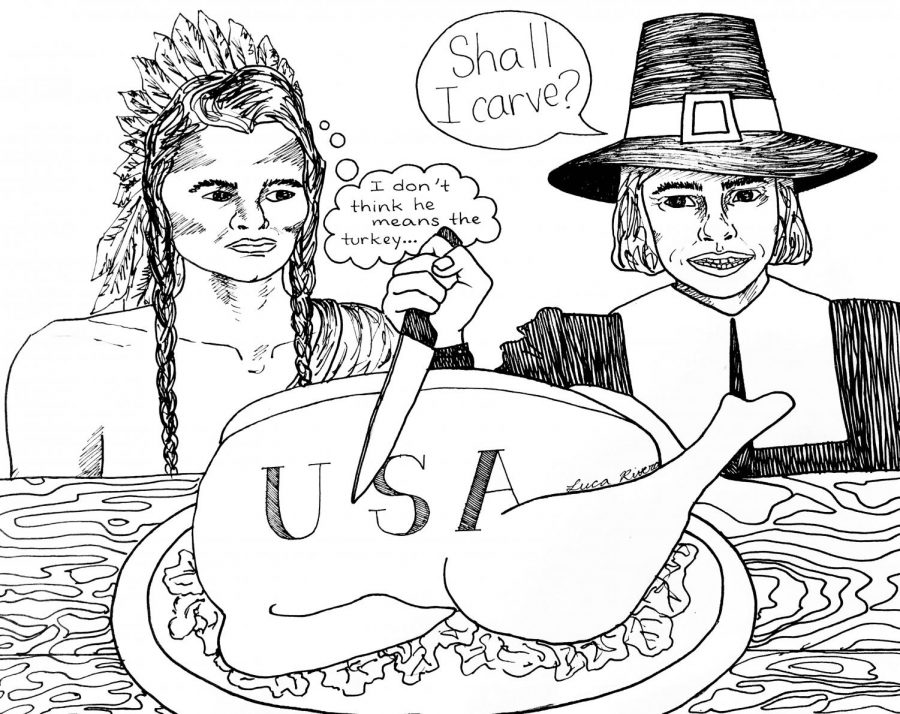

Point/Counterpoint: Rethinking Thanksgiving

November 30, 2017

In elementary school, Thanksgiving signified a commemoration of history, featuring Native American headbands and black Pilgrim hats made of construction paper. This reenactment reflects the story that inspires the holiday: in the autumn of 1621, the Pilgrims, who had arrived one year earlier, celebrated their first successful harvest in the New World by having a feast with a local Native tribe, the Wampanoag. The story is often used to show how there was cooperation between Natives and Pilgrims. However, Thanksgiving must be taken in the context of our relationship with Native Americans throughout our history. Are we giving thanks for one pleasant meal followed by centuries of persecution and bloodshed? In the same way that many are changing the way we think about the celebration of Columbus Day, as a society, we must change the way we view Thanksgiving given the harm we caused Native Americans in the past.

Although the story of Thanksgiving illustrates an example of cooperation between Native Americans and colonists, Europeans coming to America have ravaged Native American populations since the discovery of America in 1492. According to the widely accepted work of anthropologist Henry Dobyns, native populations in the Western Hemisphere were around 75 million, with 10-12 million north of Mexico. European explorers and colonists brought diseases like smallpox and measles, to which the Natives had no immunity. Dobyns estimated that this accounts for anywhere from 70%-90% of the population being wiped out.

European colonists also destroyed Native American populations and settlements through warfare. To examine this, one needs look no farther than the very Pilgrims who participated in Thanksgiving. A generation after the original Pilgrims in 1621, war broke out between Europeans in the Plymouth colony and the Wampanoag, the same tribe from the Thanksgiving story. The conflict, called King Philip’s War, resulted in massive losses for both sides. The same groups that were making peace one generation before were slaughtering each other over control of land. Furthermore, during the Pequot War, the Puritans of Massachusetts slaughtered the Pequot tribe. The colonists punished the Pequots for killing a handful of English merchants by burning down villages and brutally killing any survivors. The conflict ultimately resulted in the decimation of the Pequot tribe from Massachusetts.

Although Thanksgiving may have been a brief moment of European and Native American peace, it is overshadowed by centuries of European and American abuse of Natives. In the grand scheme of things, one day of cooperation is insignificant.

Our long-standing traditions on Thanksgiving go hand in hand with our history with Native Americans. By maintaining the same traditions, we are endorsing this history. As Americans, we should be ashamed of our history with Native Americans. Although our ancestors did the killing, it is our responsibility to make up for their mistakes. To recognize our past and look beyond it, we must change our traditions.

Instead of celebrating one day of cooperation between American colonists and Native Americans, we should also take some time on Thanksgiving to mourn all of those Native Americans who lost their lives because of white settlers. Movements like the “National Day of Mourning” protest have attempted to make this a reality in the past. The movement started in 1970, and is meant to honor Native American ancestors who died because of European colonization. As a society, we do not need to change Thanksgiving completely. Surely we have many things for which to give thanks, but a fairy tale about the peace and brotherhood between the Pilgrims and the indigenous people of America is not one of them. Let us give thanks for what we have, and for the opportunity of accomplishing and attaining the things we don’t yet have, but maybe, just maybe, it’s time to put away the construction paper bonnets and headdresses that represent a history for which we should not be thankful at all.