OP-ED: The Rittenhouse Trial and American Politics

December 19, 2021

As of November 14, Kyle Rittenhouse was acquitted on all counts: reckless homicide in the first degree, reckless endangerment in the first degree, intentional homicide in the first degree, attempted intentional homicide in the first degree, possession of dangerous weapon by a minor, failure to comply with state emergency order from state/local government. It seems almost crazy that a case with so many charges would still result in a full acquittal. While some may argue that it is the fault of the prosecution, in reality this outcome was not at the expense of the lawyers, rather, the judicial system itself. Judicial processes have become so politicized, especially those dealing with subjects like the BLM movement, that the ability to form an unbiased and fair jury may soon become an impossible task. The country is divided – this is no falsehood. Partisanship is present in all functions of civil administration and the American justice system is no exception.

Rittenhouse was 18 when he fatally shot two protesters and injured one at a BLM protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin. This case brought up a myriad of debates over, not only gun laws, but their places over state lines, the involvement of certain parental figures, and the legality of Rittenhouse’s presence in the first place. It seemed like once one topic was brought up, another two grew out of it – a hydra of political controversy. Each issue was taken as black or white; no in between.

Politics are inherent when it comes to the discussion of BLM protests. The civil rights movement in the 1960s had a strong tie to the Democratic party and this association remains. The Republican party has historically opposed demonstrations by the BLM organizations, as it has ties with being anti-police. This rejection of authority is looked on with contempt by the Republican party as the basic ideals of the party lie within “law and order”. The political implications of Rittenhouse’s actions were intense from the start, simply from Republican party ideals, and this only grew worse as the trial grew closer. On one side were the Democrats, calling Rittenhouse a domestic terrorist – someone who sought to approach peaceful protesters with the intent of harming them for his own radical agenda. The other narrative pushed by Republicans, however, was that Rittenhouse was a protector of private property who only wanted to prevent damages from violent protesters by using his Second Amendment right to bear arms.

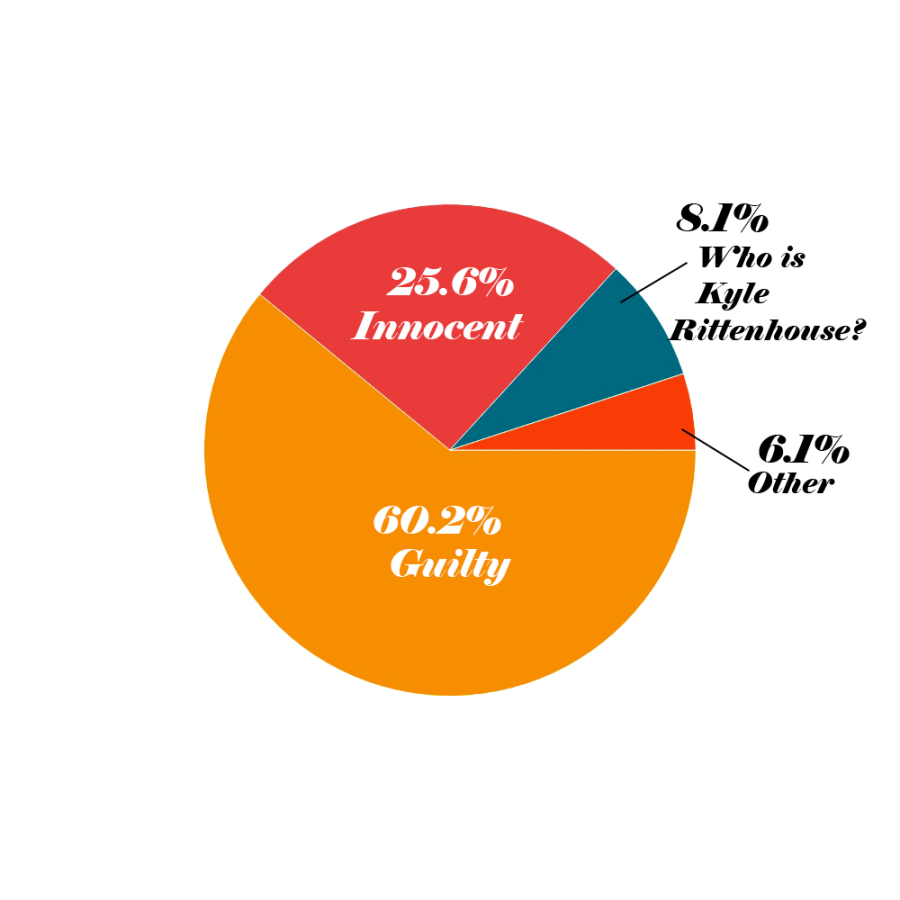

It is implicit that if you are a democrat, you would find Rittenhouse guilty and vice versa. In a survey of 211 Pelham students, 60% said that they would have found Rittenhouse guilty. For a left-leaning town, this is expected. But this result brings about an unfortunate conclusion: Rittenhouse would not have gotten the same outcome had he been on the stand in Westchester. Does that not expose a fatal flaw of the judicial system? That a man could get a result from a jury in one district, but a different one in a separate place? The issue is pressing, but it is up to debate whether there is a solution. The Rittenhouse trial is not the first, nor the last example of the intertwining and dangerous relationship between politics and justice. The fact of the matter is that truth does not have an alignment with any political party, but America faces a calamitous reality in which fact will be subject to the opinion of the people, not to the reality of events.